Vlad B. (Socialismo Revolucionario – Spanish State), 08/12/2020

The most global and perhaps deepest capitalist crisis ever is likely to bring significant changes to the way the system operates. Will this mean though a qualitative change in the economic policy of the ruling classes? After roughly 40 years of neoliberalism, are we witnessing the demise of this policy framework and a return to more Keynesian-like or other kind of state interventionist policies? Or will the neoliberal framework adapt in order to accommodate, in some countries more than in others, for increased forms of state intervention and perhaps also a more authoritarian political model? These are key questions that socialists worldwide need to grapple with.

Neoliberalism: between theory and practice

To start with, it’s important to distinguish between neoliberalism as an ideology and neoliberalism as a policy framework. Of course, the former has been used to guide and legitimise the latter, but the theory and the practice of the ruling classes don’t necessarily match. Think, for example, of the various narratives that have been historically used to justify imperialist interventions as “civilising the barbarians” or, more recently, “spreading democracy and human rights”. What we’re clearly seeing today is a sharp decline in the support for the neoliberal ideology, not only among the popular classes, but also some sections of the capitalist classes, particularly those favouring a protectionist agenda and therefore pushing for more nationalistic rhetoric in order to justify it. But we need to go beyond rhetoric. The key question at hand is whether a qualitative break with the neoliberal set of policies is on the table.

As an ideology, neoliberalism emerged about fifty years ago from the attempts of economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman to revive the discredited 19th century belief in the infallibility of the free market. State intervention in the economy should be merely limited to providing and enforcing the legal framework needed for the free market to function. Several core neoliberal principles stem from this belief:

- Deregulation of the labour market would give more freedom and flexibility to both employers and employees.

- Deregulation of financial markets would unleash their potential to generate prosperity.

- Public assets and services should be privatised, as the market would provide more freedom of choice and thus better quality than state monopolies.

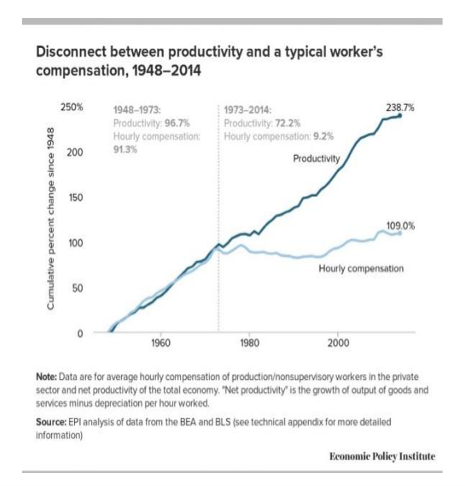

- Wage growth needs to be decoupled from productivity growth (unlike in the post-WWII era) in order to both avoid inflation and encourage investment.

- Demand should be stimulated not by fiscal policy (i.e. how the state taxes and spends in order to influence the economy) but by monetary policy (i.e. how the state controls the money supply in the economy).

- Public spending needs to be cut in order to avoid high public deficits, which in turn lead to high public debts.

- National barriers should be removed to allow for the free movement of capital, labour, goods, and services (i.e. economic globalisation).

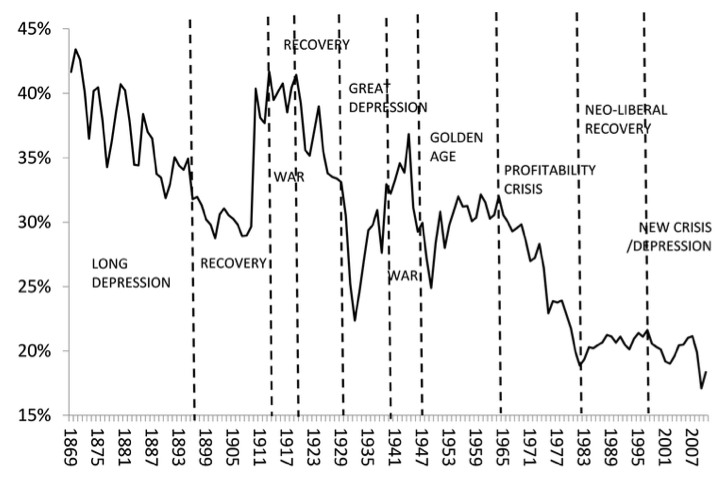

All these broad policies make it obvious that the role of neoliberalism is to protect and boost profit rates, which had started to fall in the early-to-mid 1970s. And neoliberals have never denied that but justified it through the shamelessly hegemonic concept of ‘trickle down economics’ (i.e. we all benefit if the rich get richer). Fundamentally, neoliberalism was the solution that capitalist classes came up with against the underlying, systemic problem of the historic decline in the profit rate, a problem that had been only temporarily fixed by the boost allowed by the post-WWII reconstruction. In short, neoliberalism has always been a ruling class project for the restoration of the profit rate – a return to a more authentic and brutal form of capitalism, stripped off the rights and regulations it was previously forced to concede.

The process that saw this policy framework prevail in most of the world has been uneven, both in depth and width. After being tested out in the ‘periphery’ (Chile) in the mid-1970s, neoliberalism steadily rose to prominence in the ‘core’ imperialist countries – first in the US and the UK, then in continental Europe via the institutional architecture of the EU, and Japan. Through the influence of international organisations such as the World Bank and the IMF, neoliberal policies also proliferated throughout the neo-colonial world, shaping its contemporary relations with imperialist countries. That proliferation received an incalculable boost from the fall of Stalinist regimes in 1989, which – coupled with social democracy’s qualitative shift to the right – allowed neoliberalism to claim to be the only game in town, indeed, the very ‘end of history’.

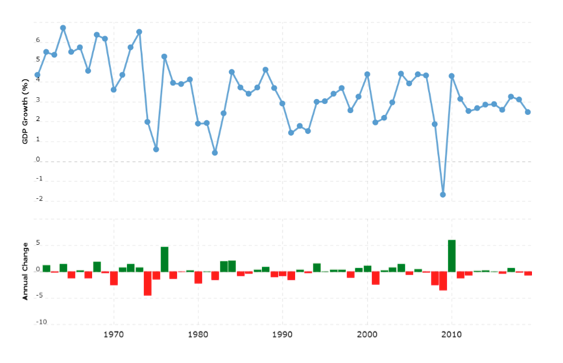

A balance sheet of four decades of neoliberalism is beyond the scope of this article. But it’s telling enough that, apart the soaring levels of inequality both within and between countries, neoliberalism has failed even by its own standards of capitalist efficiency: as illustrated by the chart below, the GDP has been growing at a much slower rate since 1980 than in the two decades before that. Moreover, that relatively slow rate of GDP growth was largely debt-driven, leading to contradictions that eventually burst out in the 2007-2008 global financial crisis and which have never been overcome since.

At the same time, like the history of capitalism in general, neoliberalism has been an uneven and combined process, where the neoliberal practice never fully matched the neoliberal theory and has always co-existed with other kinds of policies. This is particularly true of the role of the state. David Harvey aptly points that out in his useful book on the history of neoliberalism:

“The role of the state in neoliberal theory is reasonably easy to define. The practice of neoliberalization, however, evolved in such a way as to depart significantly from the template that theory provides. The somewhat chaotic evolution and uneven geographical development of state institutions, powers, and functions over the last thirty years suggests, furthermore, that the neoliberal state may be an unstable and contradictory form.”

In other words, there never was a pure ‘minimal state’, as advocated by neoliberal ideology. The state was pushed back only in those fields where it obstructed the maximisation of profit, such as welfare or public ownership. But, like any form of capitalism, neoliberalism fundamentally needs the state, not only to maintain the social order through the institutions of force (police, courts, army, secret services), but also from an economic point of view. And this often happens in direct violation of some of the aforementioned neoliberal principles.

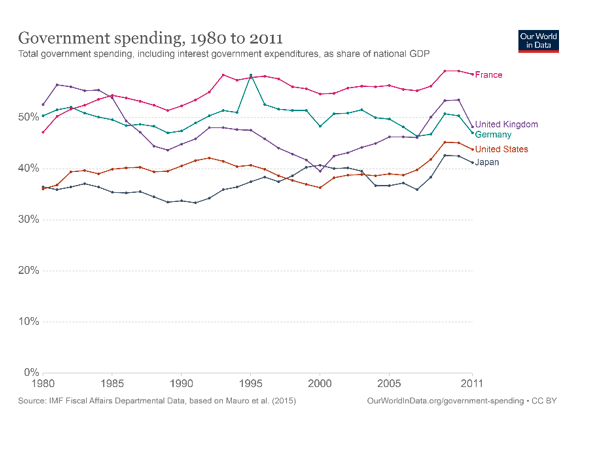

Firstly, neoliberalism has indeed rolled back public spending in areas such as healthcare, education and social security, but overall public spending increased since 1980 in countries like the US, France or Japan. The chart below shows that in the US public spending increased even under Reagan, otherwise a champion of neoliberalism. This was due to the sharp rise in military expenditure, but also to the massive subsidies given to certain sectors of the economy, particularly agriculture, the aerospace and the biomedical industries. This kind of ‘economic nationalism’ has partly increased in recent years under the Trump administration through the introduction of tariffs on certain foreign imports, but it has always been a feature of US neoliberalism.

Secondly, while the financial markets have been de-regulated to a large extent, both nationally and internationally, the state was always there to step in whenever those markets were at risk of collapse, most notoriously in the 2008 crisis but also long before that, in the 1989 savings and loans crisis in the US. State bailouts have always been a feature of neoliberalism. Moreover, the Quantitative Easing that we can see now in some countries was already used by Japan in the early 2000s, later on by the US and the UK in the 2008 crisis and then by the European Central Bank in 2015 in an attempt to boost economic recovery in the Eurozone. This didn’t prevent though neither the UK, nor the Eurozone powers to simultaneously push for draconic austerity measures.

Thirdly, despite decades of cuts and privatisations, in most developed countries the state still provides, to a certain extent, certain key services such as education, healthcare and some minimal social security. The forces of the ‘free market’ are incapable to cater for these basic needs so they rely on the state to do it, in order to ensure the social reproduction of the workforce while also containing mass social turmoil that could endanger the status quo. Even in largely privatised industries, such as in public transport, companies rely on infrastructure built and maintained by the state. For example, in Britain, direct state subsidies for the railway system have increased by more than 200% since they were privatised. And when, despite such generous gifts, the private companies still fail, the state is summoned to nationalise the industry – as illustrated recently by the case of Transport for Wales – only to re-privatise it later when the market improves. Thus, the neoliberal ideal of ‘outsourcing’ most functions of the state to private actors has never been fully implemented, precisely because capitalists structurally rely on state funding to boost their profits, from providing basic infrastructure to funding research to bailing them out in times of need.

Fourthly, the post-WWII Keynesian era that preceded neoliberalism was defined by the broad consensus that wages should grow in line with productivity, precisely in order to sustain demand and thereby sustain (near) full employment. Neoliberalism, however, has entailed a decoupling of wage growth from productivity growth, which has seen, at best, a near-stagnation if not a significant decline of real wages. For example, in the US, productivity and wages increased almost at the same pace between 1948 and 1973, but since then productivity increased by nearly eight times more than the average worker’s hourly compensation, as illustrated below.

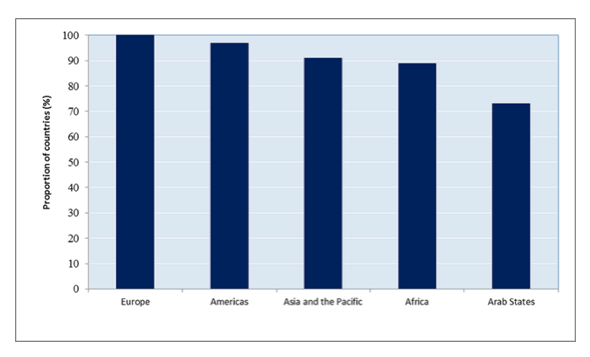

Of course, at the same time capitalists have had to try and prevent the emergence of a demand gap that would undermine their entire system, which is why neoliberalism employed the tool of cheap credit, with the well-known consequences. But in parallel some neoliberal states have also employed policies of more of a Keynesian character, such as the introduction of the minimum wage. An ILO statistic from 2015 showed that, either by legislation or binding collective agreements, 90% of all countries had statutory minimum wages. The potential introduction of a universal basic income in some countries would also fit in this category of state intervention within a neoliberal framework.

Fifthly, the state plays a key role in facilitating the free flow of capital, goods and services internationally, in what is broadly called economic globalisation. It mostly does so via diplomatic means, be it bilaterally or within the complex web of international institutions built in the aftermath of WWII, such as the World Bank, IMF, EU, OECD or, more recently, WTO. The imperialist states devising and running these institutions and their regulations need the weaker states to ratify and enforce them. However, when the system of ‘global governance’ doesn’t deliver the goods, imperialist states don’t shy away from using military intervention to promote the economic agenda of their capitalist classes, thus showing that the state is all the more central to how neoliberal capitalism works in imperialist countries.

Qualitative shift?

So neoliberalism has always accommodated other types of policies that required state intervention. Nevertheless, they were embedded in the neoliberal framework that has taken root over the last four decades. Despite its variegated and often inconsistent manifestations, on the whole that framework has meant financialisation, free trade, capital mobility, international relocation of production, privatisation, low taxation of capital, decline in the GDP share for wages, low deficit targets, cuts to public spending, ‘flexibilisation’ of the labour markets, and anti-union legislation.

At the same time, none of these policies is originally neoliberal. The main characteristics of the epoch that is described as ‘neoliberalism’ processes have been characteristic of capitalist development since its very start, with the one big exception of the so-called Keynesian era that lasted from the 1930s to the 1970s. What is new about neoliberalism has been the qualitative change in many of these policies. Financialisation, for example, was also a feature of the imperialism analysed by Lenin, but the shift from productive sectors to financial firms as share of overall corporate profits was not. Also, while globalisation is an old historical process deeply intertwined with the history of capitalism, neoliberalism has accelerated it to the extent of an unparalleled level of international economic integration.

Today, we are witnessing large-scale state intervention triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, in sharp contrast with the neoliberal myth of the ‘self-regulating free market’. We are also witnessing increasing rejection of neoliberal policies among all classes, particularly among workers and the precarious youth but also from small entrepreneurs on the verge of bankruptcy and even big capitalists who find it increasingly hard to keep up with their competitors from other countries. They all call for state intervention in one form or another. Such calls have also been echoed in the capitalist media, including the Financial Times. More ‘progressive voices’ went farther and claimed that “Coronavirus spells the end of the neoliberal era”. Is that the case? Is the rise in state intervention, including protectionism, a sign that we are witnessing the end of neoliberalism?

The demise of the neoliberal framework would require a qualitative shift away from all or at least most of the policies that compose this framework. To break it down, it would require a qualitative shift from:

- privatisation to (long-term) nationalisation;

- de-regulated to regulated industries;

- austerity to sustained mass public investment;

- capital mobility to capital control;

- low taxes to high taxes on corporations and the very rich;

- real wage stagnation to wage growth in line with productivity;

- precarious jobs to secure and unionised jobs;

- free trade to protectionism.

If by a qualitative shift we understand a shift that is substantial in terms of duration (i.e. not temporary), extension (i.e. not limited to a handful of countries from one or two regions of the world) and depth (i.e. not limited to only a few sectors of the economy), then there is little evidence as yet that a majority of these shifts identified above are likely to happen in the coming period. There have been visible rises in state economic intervention (centred around the COVID-19 pandemic) and protectionism (centred around the US-China inter-imperialist tensions). However, as pointed out above, these trends have always had a place within the neoliberal framework, particularly in the stronger imperialist countries. It is again in these countries, such as the US or the UK, where we have witnessed, in the recent period, the most significant rises in state intervention and protectionism. But even there these trends are far from prevailing over their neoliberal opposites.

State investment?

There is little reason to believe that the exceptional state stimulus packages that we have seen in reaction to the economic paralysis caused by the pandemic are likely to become the new norm for the capitalist classes. They are rather exceptional measures in exceptional times. Furthermore, only a handful of rich countries are able to sustain them for any sustained period of time. Most countries will resort to cuts in public spending as early as next year if they have not done so already. A recent review of the IMF reports on the 80 countries (mostly from the neo-colonial world) it has given financial assistance to between March and September of 2020 paints a grim picture, with austerity set to define fiscal policy for most of these countries in the coming years. These three findings are particularly relevant:

- “72 countries are projected to begin a process of fiscal consolidation as early as 2021. Tax increases and expenditure cuts are to be implemented in all 80 countries by 2023.

- 59 countries have fiscal consolidation plans over the next 3 years that are larger than the Covid-19 response packages implemented in 2020. Fiscal consolidation represents 4.8 times the amount of resources allocated to Covid-19 packages in 2020

- For 46 countries for which data is available, a decade of austerity measures will reduce public expenditures from 25.7 to 23 per cent of GDP between 2020 and 2030.”

Even in richer regions, such as the EU, austerity will not be going away any time soon despite the larger scale of state intervention facilitated by international funds such as the European Recovery Fund. The money from the latter will come attached with conditionalities, such as the ‘reform’ (read privatisation) of the pension system in Spain. Furthermore, the so-called ‘frugal countries’ (Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands) that together with Germany dominate the Eurozone have reserved the prerogative to block the transfer of money in case the ‘reforms’ do not take place as they see fit, thus reflecting the deeper North-South cleavages within the EU that this crisis is likely to accentuate. At the local level too, austerity is set to continue. For instance, one of the biggest local authorities in the UK, the Greater Manchester Council, has been recently considering implementing “a catalogue of cuts not seen since the worst years of austerity”.

Last but not least, we need to be clear about the character of the state intervention that we are witnessing. As tempting as the parallels with the 1930s New Deal may be, there is no real ground for them. The New Deal saw in the space of five years one of the largest cases of state-led investment ever seen in the history of capitalism, as aptly summed up by a recent text on this topic:

“Within just a few months, a wide range of employment programmes was put in place that led to the deployment of more than six million of the hitherto unemployed to work on the construction of schools, playgrounds, nursery schools, roads and parks and on reforestation and landscape preservation programmes. Wide-ranging infrastructure projects were implemented, resulting in the construction of major barrage and dam systems for the cultivation, irrigation and electrification of entire regions. … And last but not least, 3,000 creative artists in various disciplines were given state support to bring the arts to the people.”

That kind of state intervention, by which the state itself creates millions of jobs and new infrastructure along with that, is not what we can see at the moment or are likely to see in the coming period. We need to look at actual policies rather than the wishful thinking of some bourgeois analysts. What we do see, apart from the temporary furlough schemes, is the so-called Quantitative Easing, by which the state buys government bonds and injects liquidity in the banking sector in the hope that the latter will enhance lending to businesses, which in turn would lead to job creation. This type of state intervention happened before within the neoliberal framework, first in Japan in the early 2000s and later on in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, particularly in the UK and the Eurozone.

The same goes for the kind of nationalisations we can see at the moment. As before in the history of neoliberalism, the state nationalises some private companies only to cover their losses and prepare the ground for their subsequent re-privatisation, as we saw happening with the banks in the previous crisis. During this temporary nationalisation, the state doesn’t exert any real control over how these companies operate, whose management boards are allowed to lay off workers in order to restore profitability.

A new protectionist era?

When it comes to the rise in protectionism, we need to ask ourselves similar questions. Is it likely to become the dominant global trend in place of the ‘free trade’ trend that dominated the post-WWII and particularly the post-1989 era? How many countries can afford the ‘luxury’ of imposing tariffs and other barriers to trade apart from the two biggest imperialist powers, USA and China? For instance, the economies of most Central and Eastern European countries are overwhelmingly dependent on the international supply chains. For Slovakia, Slovenia or Hungary, exports represent over 80% of their GDP. That number is higher than the GDP itself in the case of Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam or Singapore.

COVID-19 pandemic triggered a dramatic decrease of 9.2% in the volume of world trade in 2020. However, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) estimates a rebound of 7.2% in 2021. More interestingly though, the pandemic has triggered, in relation to the virus, further liberalisation of trade, as shown by this other WTO report:

“Of the 133 COVID-19 trade and trade-related measures recorded for G20 economies since the outbreak of the pandemic, 63 per cent were of a trade-facilitating nature and 37 per cent were trade restrictive. Almost three out of every ten COVID-19 restrictive measures on goods taken by G20 economies had been repealed by mid-October. Most of them were export restrictions. In the services sectors heavily impacted by the pandemic, most of the 68 COVID-19 related measures adopted by G20 economies appeared to be trade facilitating.”

Even the two largest economies in the world, the USA and China, can only go that far with their protectionist measures, mostly taken against each other. Firstly, those measures do not prevent either of them from pursuing tighter economic relations with other countries or blocs of countries. Decoupling does not necessarily entail de-globalisation. Indeed, in September we witnessed “the first significant bilateral trade agreement signed between the EU and China”, while more recently Germany went against its US ‘ally’ by allowing Huawei to develop part of its 5G network. More importantly, a few days after Chinese President Xi Jinping “called for a more constructive approach to an open global economy, and hit out at protectionism”, China and 14 other countries from the Asia-Pacific region signed in mid-November the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Considered to be “the world’s largest free-trade deal, representing 30 per cent of global GDP and 30 per cent of the world’s population”, this will entail further pressure on workers’ wages and rights in the region. Of course, on the background of the recent tensions between the US and China, this deal will face important limitations and contradictions, as shown for instance by the tariffs imposed a few days ago by China on Australian wines. But precisely given the US-China tensions, it is still significant that RCEP is the first collective agreement that brings together countries with traditionally divergent geopolitical allegiances, such as China, South Korea, Japan and Australia.

Secondly, even those inter-imperialist tensions are not straightforward. The trend of economic decoupling between the US and China is only part of the picture, that part which reflects the interests of those sections of domestic US capital that want more protection from their state. Trump has been their political representative. However, even he was severely limited in how far he could go with the economic nationalism he demagogically professes. Not only he failed to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US, but almost 1,800 plants have been offshored in the first two years of his administration alone. The transnationally oriented sections of US capitalism still prevail and still need globalisation. The likes of Apple heavily rely on the highly skilled labor that is available in China but not – at least numerically – in the US. As the tech giant’s CEO put it back in 2017:

“The products we do require really advanced tooling, and the precision that you have to have, the tooling and working with the materials that we do are state of the art. And the tooling skill is very deep here. In the U.S., you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I’m not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields.”

These structural factors have not changed since. While some of Apple’s OEM partners, such as the Taiwan-based Foxconn, have recently shifted some of their plants away from China due to the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration, those plants still represent a small fraction of the 380 suppliers that Apple had in China as of 2018. Even the re-location that has occurred so far has been anything but a form of protectionism: Apple is not shifting production back to the US but to countries like Vietnam, which provides a similarly qualified labour force as China, but at cheaper costs. Indeed, in reaction to that, the authorities in Zhengzhou, the Chinese city most affected by this re-location, have already agreed in September to give Foxconn further tax rebates. What this means, even more so in the context of RCEP, is a race to the bottom between countries in the region to lower taxes and workers’ wages in order to attract private companies. In effect, it means more neoliberalism.

At the other end of the decoupling trend between US and China, a key factor will be of course the foreign policy of the new Biden administration. This will primarily stem from the economic interests of those transnationally oriented sections of the US capitalist class that – in contrast to Trump – Biden represents. Internally too, as our comrades in the US have pointed out, the Biden administration “will resist any serious proposal to tax the rich and big business and they will seek to maintain as much of the neoliberal agenda as they can”.

Finally, the example of Apple tells a bigger story about the character of world trade today. Shifts from ‘free trade’ to protectionism, or vice versa, have happened before in the past, like in the 1930s. But back then, international trade mostly consisted of countries buying and selling different manufactured goods to one another. Since the 1960s and 1970s though, a fundamental change has taken place: an increasingly higher share of trade consists now of intermediate inputs rather than final goods. This reflects the unparalleled degree of the fragmentation of production and integration of supply chains. As of 2018, for instance, Apple officially had suppliers from 28 countries, including – apart from China – Brazil, Mexico, Germany, Belgium, Japan, Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia etc. This is part of the growing trend in recent decades of the so-called Intra Industry Trade (IIT), which means a country is simultaneously importing and exporting goods in the same industry. In turn, this means that the introduction of nominal tariffs is more limited than ever before.

In sum, the expansion of economic globalisation since the Second World War and particularly since the end of the Cold War has led to a level of economic integration never witnessed before in the history of capitalism, both quantitative and qualitatively. The rise in protectionism and geopolitical tensions will likely lead to a partial reconfiguration, or realignment, of globalisation as we know it. But the capitalist classes worldwide, even their domestic protectionist wings, have limited space of manoeuvre to shift decisively towards ‘economic nationalism’ (which in itself would still be compatible with most elements of the neoliberal framework). That space is all the more limited for peripheral and semi-peripheral countries; but even the most powerful states currently lack the objective basis for any return to past eras of national self-sufficiency, as the last minute attempts of the British government to secure a trade deal with the EU is showing us these days.

State repression and authoritarian neoliberalism

Capitalism is entering one of its biggest crisis ever from a very weak economic position, after years of sluggish growth and toxic financial practices, all on the background of a historic decline in the rate of profit, as illustrated below. As the competition over markets and resources intensifies, so do the contradictions within the capitalist class, broadly divided between small-to-medium capital, objectively oriented towards the internal market, and big capital, objectively oriented towards external markets and international supply chains. However, as shown so far, there are no signs that either section of the capitalist class is prepared to push for a qualitative break with neoliberalism even if they wanted to.

Source: https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/a-world-rate-of-profit-a-new-approach/

While the increase in trends running counter to neoliberal principles have visibly increased in some countries, they are not yet looking to become dominant. Thus, it is more likely for such trends of state intervention to be further accommodated, as in the past, within the general framework of neoliberal globalisation. Thus, more or less temporary stimulus packages (including measures like the universal basic income) and protectionist measures will be accompanied by further austerity, further privatisations, further attacks on workers’ wages and rights, further deregulation of markets, further financial speculation, further accumulation of debt.

The more significant change though is likely to happen at a political level. Although it started as an experiment under the right-wing military dictatorship of Pinochet, neoliberalism largely used rule-based liberal democracy and international cooperation as its predominant political methodology. After 1989, the two were sold as ‘2 in 1’ to the masses of Central and Eastern Europe and countries in the neo-colonial world. The ‘freedom of the market’ and ‘political freedoms’ were tightly linked together and supposed to feed upon each other. However, the rise of right-wing, authoritarian populist leaders like Orban, Trump, Bolsonaro or Modi signal a shift away from that model. While some of them have also employed certain protectionist measures (although coupled with policies very favourable to foreign corporations, as in Hungary or Brazil), their emphasis has been on nationalist rhetoric and anti-democratic attacks. Indeed, this trend goes beyond the aforementioned cases, as seen most recently in France with the proposed security law.

This turn has been dubbed by some left-wing analysts as ‘authoritarian neoliberalism’ – an growing divorce between the economic framework of neoliberalism and its traditional political model. It includes attacks on the oppressed groups, an increase in policing and the violence that comes along with it, as well as measures that undermine the traditional tenets of liberal democracy, such as the separation of powers or freedom of press. Many if not most mass protests that we have witnessed in the recent period, particularly in Poland and France, have been triggered by such attacks. At a more structural level, authoritarian neoliberalism also entails a removal of economic policy-making from the formal structures of parliamentary democracy, best illustrated in recent years by the undemocratic handling of Greece during the Eurozone crisis.

In sum, the main shift that we are witnessing in relation to neoliberalism is from liberal democracy to authoritarianism, from manufactured consent to blatant coercion. What explains this shift is precisely the sharply decreasing legitimacy of most neoliberal policies in the eyes of popular classes around the world. Now more than ever in the past 40 years, capitalist elites have to defend those policies in the face of brewing pressure from below. That pressure will build up exponentially with the economic crisis triggered by COVID-19, as we have already seen on virtually all continents in recent months.

However, the current weakness of the labour movement and of the left in most countries means that many of the mass struggles that will emerge in the coming period will lack the organisational vehicles to grow and develop into the much needed political alternatives to the forces of capital. The Arab Spring that started nearly a decade ago was, despite its epic proportions, a painful illustration of what such an organisational vacuum leads to. That vacuum persists in most parts of the world. Despite the worsening objective conditions, the basic organisations of the working class, the trade unions, are qualitatively weaker numerically, organisationally and politically. Most young people coming to politics today do not see trade unions as their organisations.

Also, the revolutionary left is still marginal and the mass workers parties of previous decades have not been rebuilt. Indeed, in a number of countries, particularly in Southern Europe, the retreats or outright capitulations of neo-reformist left formations in recent years will have an impact on the ability of our class to benefit on a short-to-medium term from the current crisis. In many countries, the populist and nationalist right is a more significant factor than in the previous crisis and may therefore be better positioned to capitalise on people’s anger against the establishment in the coming period. It is important for socialists to point out and explain the obstacles and potential defeats ahead of us. This is not to demoralise the people but arm them with a sober and balanced analysis precisely so that they are not demoralised by the obstacles and potential defeats.

Opposite trends always co-exist but sharply intensify in times of crisis, although at different degrees from country to country. Any potential gains for the right will occur simultaneously with an acceleration of radicalisation to the left, away from the currently prevalent illusions in reformist, Keynesian solutions to the capitalist crisis. The right’s own lack of genuine solutions to people’s problems and its real class allegiance will kick in sooner or later, opening up new, ever greater opportunities for mass struggles. It is from these struggles that new organisations of the popular classes will emerge to provide the necessary socialist and internationalist alternative to all versions of capitalism.

https://net.xekinima.org/neoliberalism-demise-or-adaptation/